Don Weaver points out his name in a vintage racing program to Andrew Layton. Torrance, California, April 12, 2014.

Stories of Speed

by Andrew Layton

Don Weaver – Master of Opportunity

If you’re ever in Torrence, California on a Saturday morning, go to Hof’s Hut. It’s a breakfast joint on Crenshaw Boulevard known for pancakes, waffles and pie. You’re likely run into Don Weaver, one of the “regulars.” At eighty-four, Don doesn’t get around as well as he used to. Strike up a conversation, though, and you’ll see his face glow with the determination and passion that has driven a career in professional auto racing for over six decades.

Don Weaver points out his name in a vintage racing program to Andrew Layton. Torrance, California, April 12, 2014.

The gritty magnetism of Gilmore made Don realize that he couldn’t be content as a mere spectator. “I used to sit up in the grandstands,” he remembers, “and I said, “I don’t want to be up here, I want to be down there – in the pits!” A chance encounter with Harry Meyer – brother of the Lou Meyer, of the legendary Meyer-Drake “Offenhauser” engine – changed the direction of Weaver’s life.

Of course, Don tells the story best:

The midget Harry owned was painted with house paint. He just took rollers and went over it – it was horrible. He needed somebody to paint his car for him, but he was too cheap to pay anybody to do it. So I’d listen to the conversations going on in the pits, sitting way up in the grandstands in turn two. This guy’s talking, this guy’s listening, this guy’s saying that. “Hmmm. That guy’s Harry Meyer,” I thought. He don’t know it, but I’m gonna paint his car.” So I go down there after the race is over, and I said “Which one of you guys is Harry Meyer?” He said, “Well, I’m Harry Meyer.” I said, “You know, I come out here every night, and you’ve got a very unique car, but it’s got a lot of trouble. Would you be offended if I offered to paint it for you for nothing?” He said, “Come here, kid,” and that’s all it took!

Suddenly, Weaver was working as an apprentice – or “stooge” – alongside some of the finest wrench-turners in auto racing. When Meyer’s pit crew grew beyond Gilmore’s five-man limit, Weaver connected with Art Boyce, a talented driver-mechanic who by day served as caretaker of the ambulance fleet at Harbor General Hospital in Torrance. Art had been hired by El Monte supermarket owner Ray Crawford to prepare and house a midget for the 1947 season and needed a capable assistant.

At Culver City Stadium during a radio broadcast, circa 1948. (L to R) Art Boyce, Don Weaver, Ray Crawford, and Bill Welsh, a local newsman and commentator. Crawford, a P-38 fighter ace in World War II and Captain in the Air Force Reserves, usually raced in a flight gear, pulled over a luxury business suit. (Roy C. Morris Collection)

But as Weaver’s skill grew, he found himself lost in the crowded sideshow of Crawford’s pit. With a keen eye for opportunity, Don began watching a sullen driver from Fresno who arrived at the track early to work on his midget – alone. His name was Bill Vukovich. “I didn’t ask Vukovich if I could help him,” recalls Don. “I watched what he did. Pretty soon, I had all his little idiosyncrasies down.” Finally, Weaver told his mentor Art Boyce that he intended to leave Crawford’s team to work with Vukovich. His reply: “You gotta do what you want, Don.”

Weaver’s relationship with Bill Vukovich was steely and strictly professional – a 180 degree turn from Crawford’s good-natured generosity. “[The first time I helped Vukovich] I just went over there and grabbed his bumper. He steered it, and I pushed. Then he turned around and went, “Ug,” I did this with Vukovich and all he’d ever do is grunt at me.” Getting into the pits was suddenly much more difficult than it had been on Crawford’s team – and that’s where Weaver’s iron-cast determination came in. “Ray always paid my pit passes,” said Don. “Now, I’d go to the pit gate and say, ‘Did Vuky leave me a pit pass?’ The answer was always no. Somehow, Don always managed to sneak in.

Like many in the auto racing community, the death of his hero in the 1955 Indianapolis 500 left Don left permanently scarred. “Boy, that bothered me,” he admits. “When Vuky got killed, I blamed Al Keller. He went into turn two, lost control, got in the grass and couldn’t control the car. He tried to drive the car back on the cement, but there was no room. I used to hate him for causing Vuky’s accident.”

By then, Weaver himself knew what it was like to have a close brush with fate. His career had taken a brief interlude in the early 1950’s while serving overseas as an Army machine gunner during the Korean War. To this day, Don cites his experience as a racing mechanic as the reason he made it home. “We had to go take a hill one time,” recalls Don. “We got to one spot where it goes straight up and I said, ‘I’m gonna make it if it kills me.’ So we get up to the top of the hill and it’s the wrong hill! So I live another day – to race another day – because they brought us back down for a regimental party – ice cream and beer. Well, I don’t drink beer and I wasn’t gonna eat any melted ice cream. So way down at the end of this island I see these airplanes, Cessna L-19’s. I don’t know what they are, but I know that they’re mechanical things – and airplanes and race cars have a lot to do with each other. So I head down there and there’s this one guy working on one airplane, and I’m looking at it asking questions. He said, ‘Well, you know all about these things!’ I said, ‘It’s the first time I’ve ever seen one, but I used to be a race car guy out in California.’ He says, ‘Come with me,’ and he drags me to this tent and says, ‘Captain, this here’s my replacement!’

Don admits having no idea how it happened, but somewhere in the Army’s dense cloud of red tape, a transfer was arranged that put him in the aviation section. He would now be responsible for maintaining two Army observation aircraft without any formal training as an aircraft mechanic. But with time – and the application of his racing experience – Don figured out how to fuel and taxi the aircraft himself. Word later came that Weaver’s machine gun quad had been entirely wiped out by communist forces just two days after his transfer had gone into effect. “That saved my life,” says Weaver, “and I’ve been happy about it ever since – and sad, when I think about those guys and how I should have been there.”

Back from the Army, Don pooled $900 with his brother Bob to purchase an aging midget car that Jimmy Bryan had once driven at Gilmore as the Baker-Frinke Special. “Nobody could make that car work because water had rotted out the frame,” said Don. After a complete overhaul and some patented ingenuity, Weaver had the car race-ready again. He and Bob fielded it throughout the late 1950’s and into the 60’s, often with Don at the controls himself.

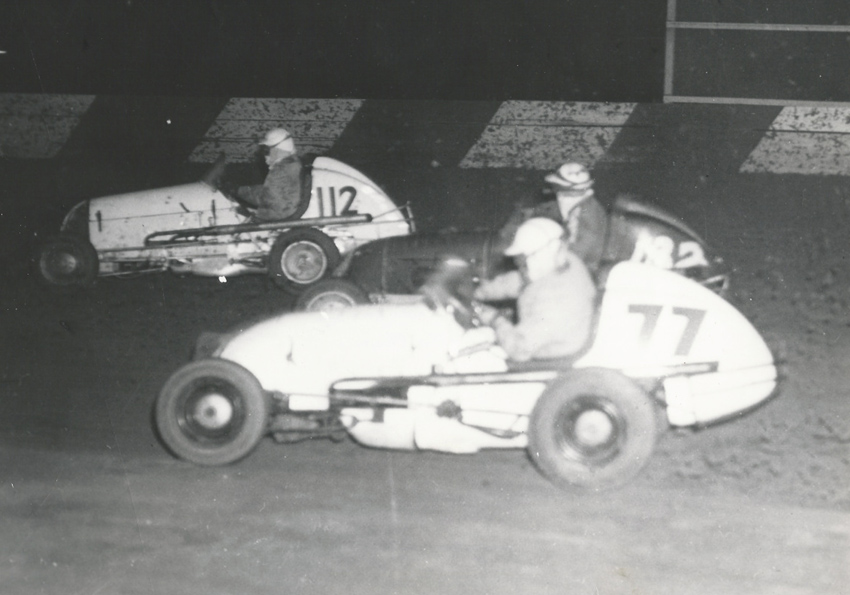

Don (#82) does battle at Culver City in the early 1950s against Chuck Hulse in Earl O’Farrell’s #112 and an unknown driver in #77. (Roy C. Morris Collection)

Bobby Unser in the South Bay Auto Body Special, owned by Don (left) and Bob Weaver (right). Photo taken sometime in 1963. (Don Weaver Collection)

Weaver’s next decade was largely consumed by his association with Vel Miletich, a car dealer from Torrence, California who had teamed with 1963 Indy 500 winner Parnelli Jones to form a potent livery that would field cars successfully at the highest levels of racing. Weaver built and occasionally crewed Miletich’s midget – driven by Allen Heath – although he was still fielding his own midget simultaneously. “Having my own car to take care of, I didn’t have much to do with Vel’s car,” said Don, “except if they needed something, I was there to do it.”

From left, Parnelli Jones, Don Weaver, Allen Heath and a Japanese dignitary with Heath”s midget. (Don Weaver Collection)

During the race, Weaver served as inside fuel man, opposite longtime Miletich partner Jimmy DIlameter. Tingelstad ran well until valve troubles put him out on lap 155. Weaver recalls part of the issue that ended Tingelstad’s day: All I had to do to fuel the car was plug in, hook on, turn on, and open a valve that would let air would come in. But my fuel wasn’t going in. What somebody did was stick rags in the hole, so when we tried to put gas in the race car, it wouldn’t go in. I said, “hold it, hold it” but they didn’t hold it. The car started to roll out, right then. I didn’t get the valve in the top shut, so it was about to run me over as I was trying to undo the valve. But at any rate, away he went.

Several laps later, Lloyd Ruby pulled his car into an adjacent pit, giving Don a front-seat vantage point to a bizarre doubling of the Johnny Lightning crew’s trouble: I’m looking down the track a few laps later to Lloyd Ruby’s car. The crew’s getting ready and whoever the chief mechanic was said “go.” Well, the way they did their fuel, they ran a tube across from the left side to the right side, and they filled it on the left side. When they waved him to go ahead, he wasn’t done fueling, either. So he took off. When he did, that hose pulled the whole side of the car out, and I could watch it tear into the aluminum – in fast time. I could see all of the fuel coming out, hitting the ground and bouncing up. That night when we went back to our hotel room, a little place we rented for the gang – holy cow – I saw that whole thing in slow motion. The fuel coming out, gushing out of the hole, tearing the whole side of the car out. I saw it all in slow motion and I said, “That’s amazing.” Your brain is speeded up so fast when you’re on that racetrack, and you’re doing all this stuff, moving so quick, and trying to get everything done as fast as you can. You’re up to another plateau. When that happens, you see everything in flash time. It’s amazing. It’s uncanny, but that’s how it works. All the drivers and all the owners and all the crewmen see everything in fast time. Tingelstad finished the 1969 Indianapolis 500 in 15th position, which was incidentally Weaver’s only chance to work in the hallowed spaces of Gasoline Alley.

Don Weaver’s involvement with auto racing has continued into the 2000’s, with the creation of a popular event called “Legends of Ascot” to celebrate the drivers and mechanics that cut their teeth on the Southern California dirt track. “I started it,” says Don, “because for all the years that these great drivers ran there, no one was doing anything to remember it.” He points out that Ascot Park was once as significant to team owners as it was drivers – if an up-and-comer hadn’t yet raced the challenging dirt tack, he was seldom perceived as being ready for Indianapolis. Weaver is obviously proud of his celebrations – and for good reason. Held annually from 2003 to 2012 – were attended by some of the biggest names in racing, including Andy Granatelli, Linda Vaughn, and of course, Parnelli Jones.

Although Don is slowing down some – “My health says, ‘You ain’t doing that no more,’ so I tried to talk to my health, but my health wouldn’t change its mind” – he still looks ahead with the same quickness of mind that seized the opportunities that began his career. “I’m so glad I decided to get down from those turn two seats that night at Gilmore,” said Don, smiling over his pancakes. “It doesn’t matter who you are or what you are – if you want to be something, you will work at it.” END

Don Weaver with a pretty lady?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|