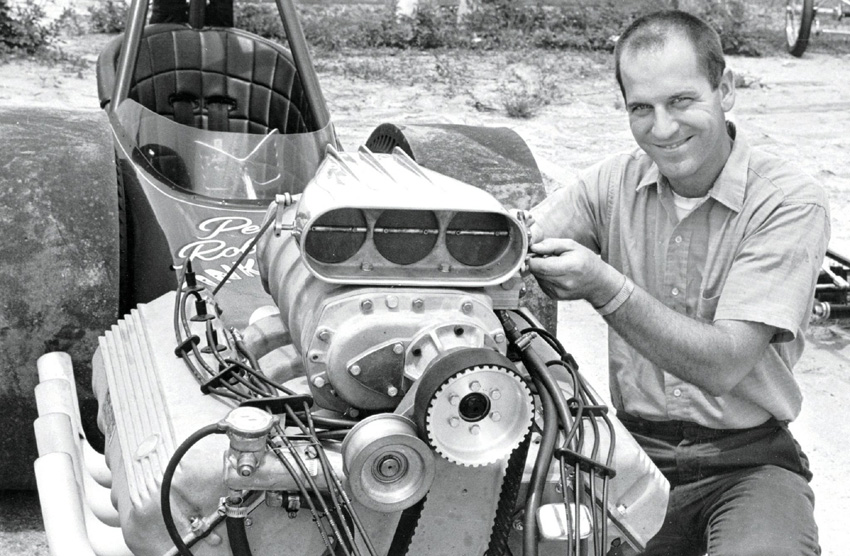

Pete

Pete

Pete

Pete

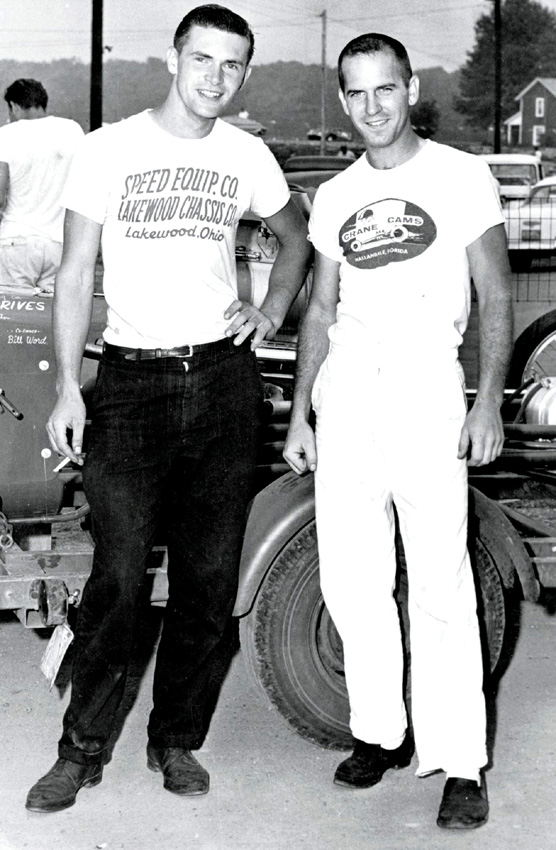

Pete and Joe Schubert

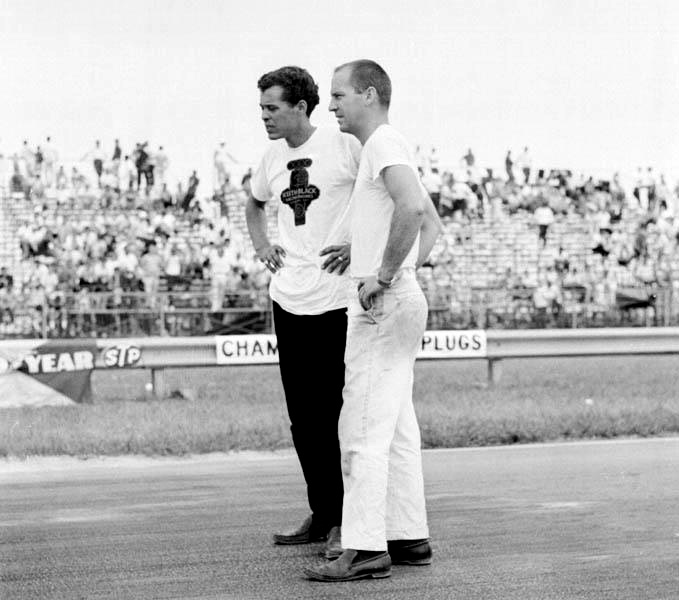

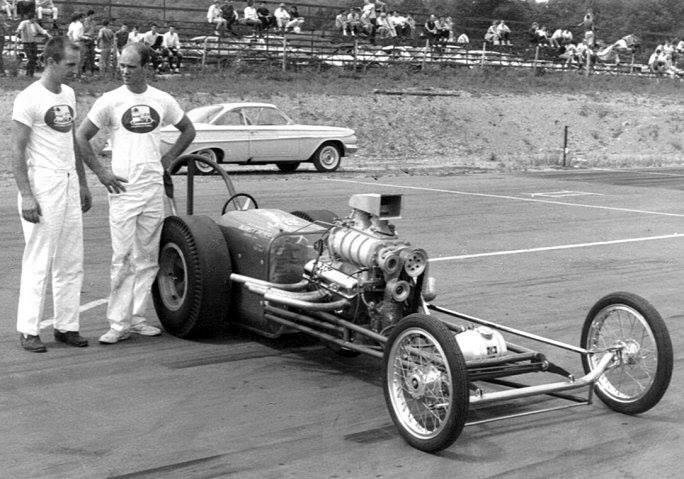

Pete and Don Prudhomme

Pete with the blue car

Pete with his ride

Pete anddf Connie Kalitta

Pete firing the car on the rollers

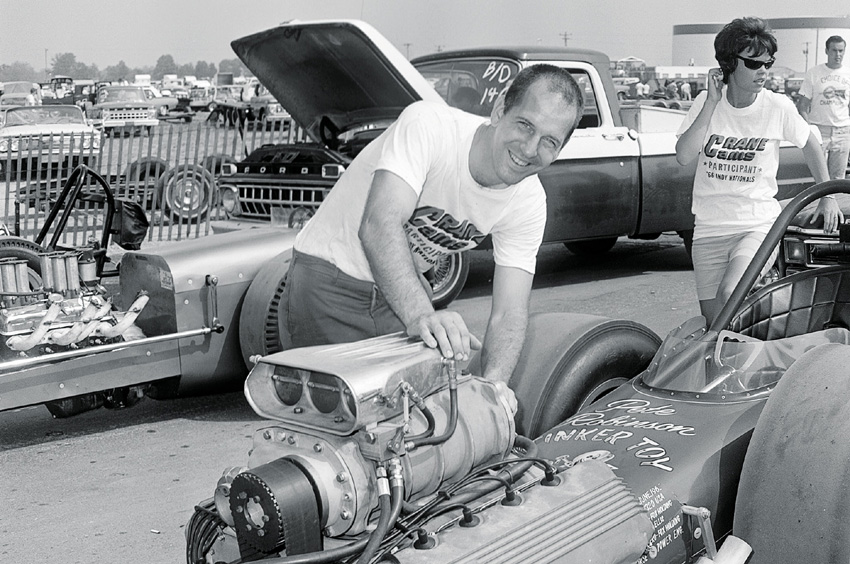

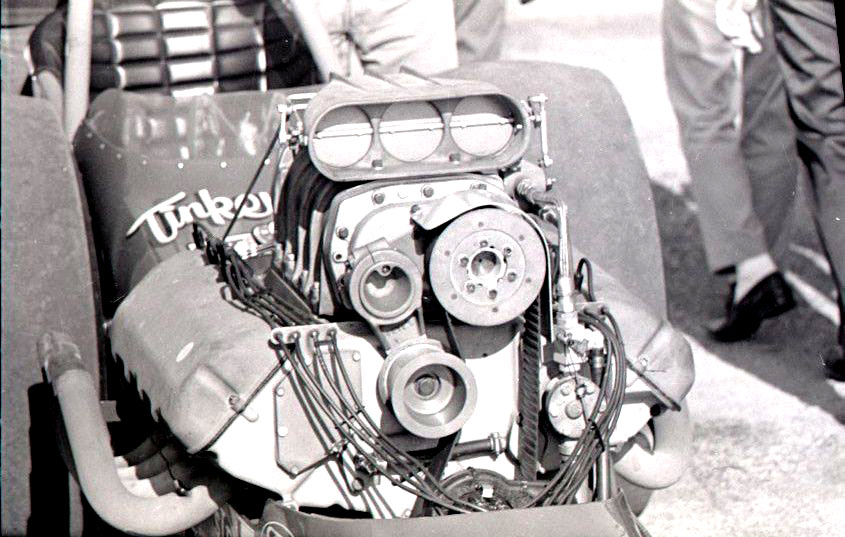

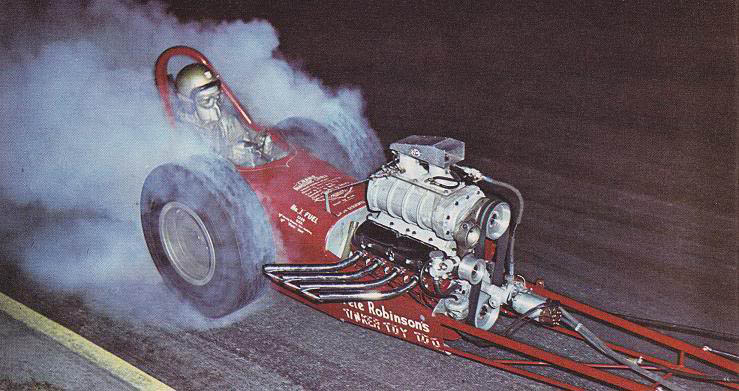

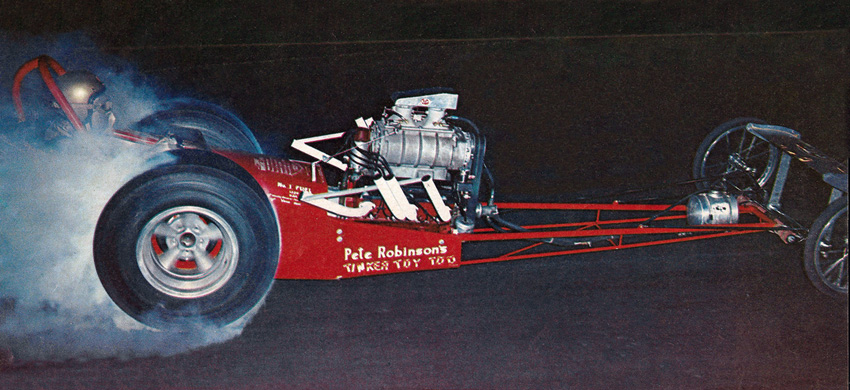

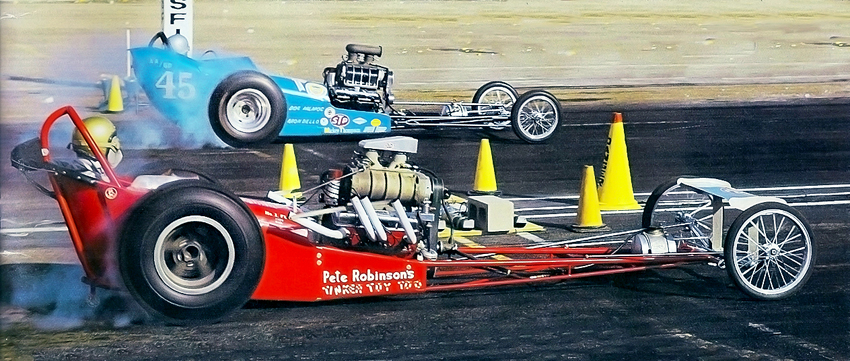

Pete in the Tinker Toy

Pete getting h/in hsi car

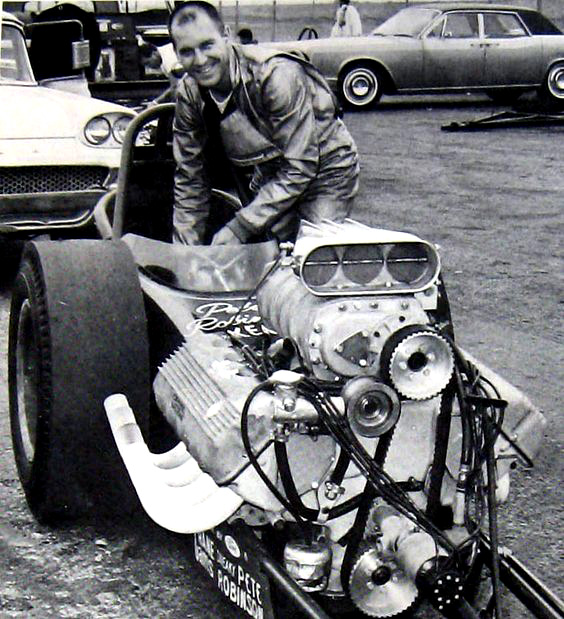

Pete with his car

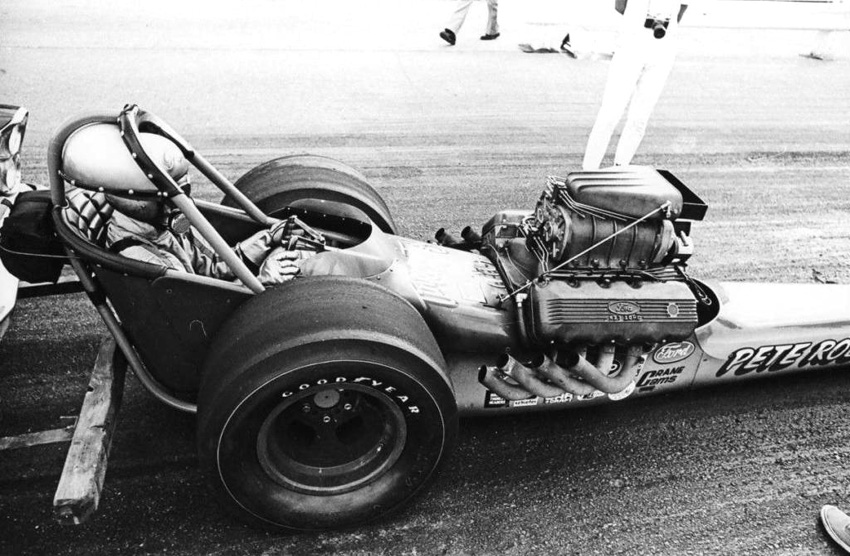

Pete in his car

Pete by his little chevy

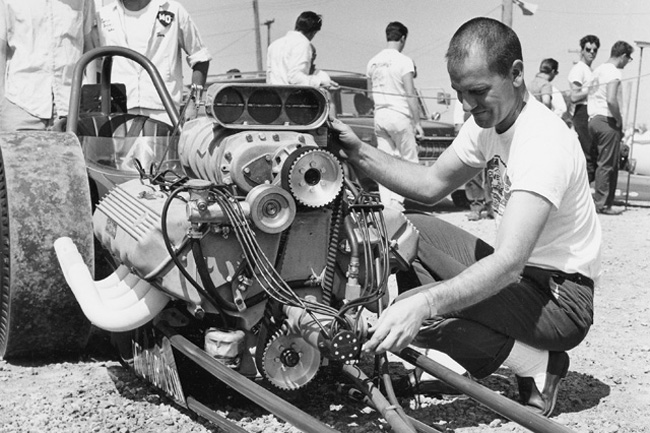

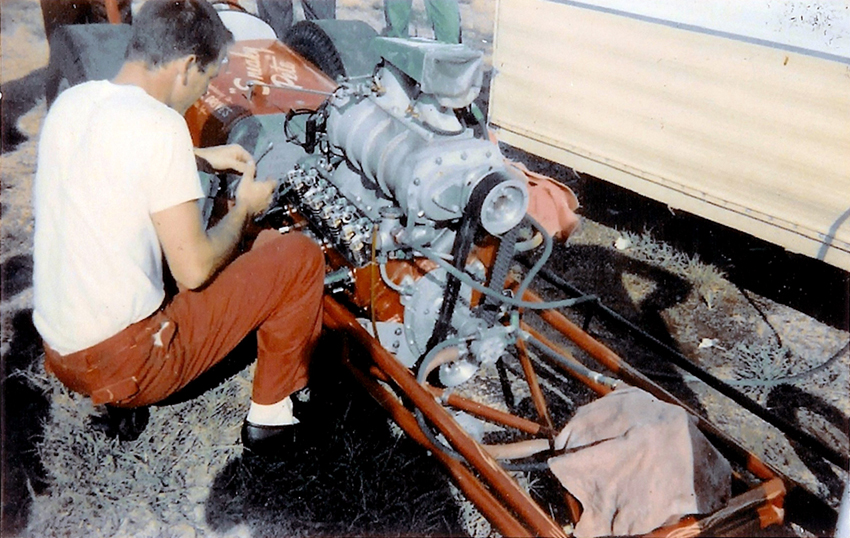

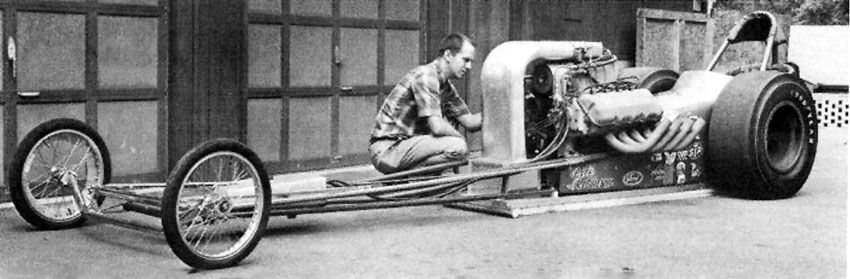

Pete working on the car

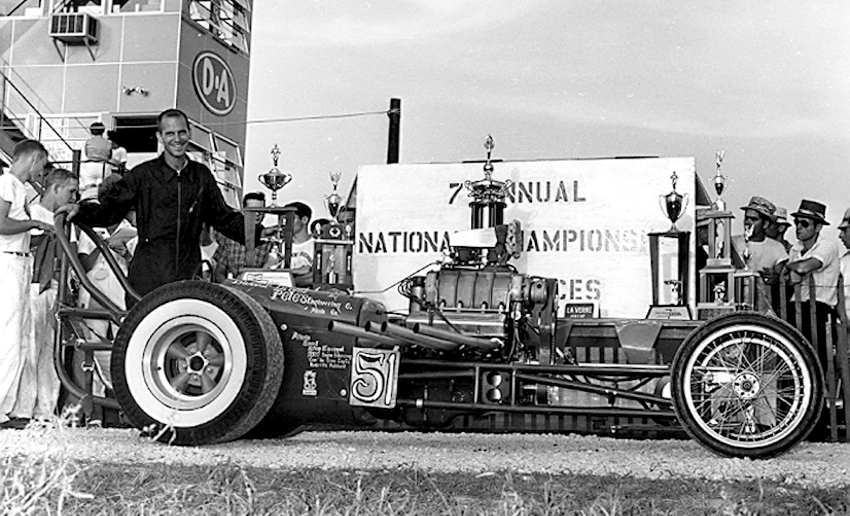

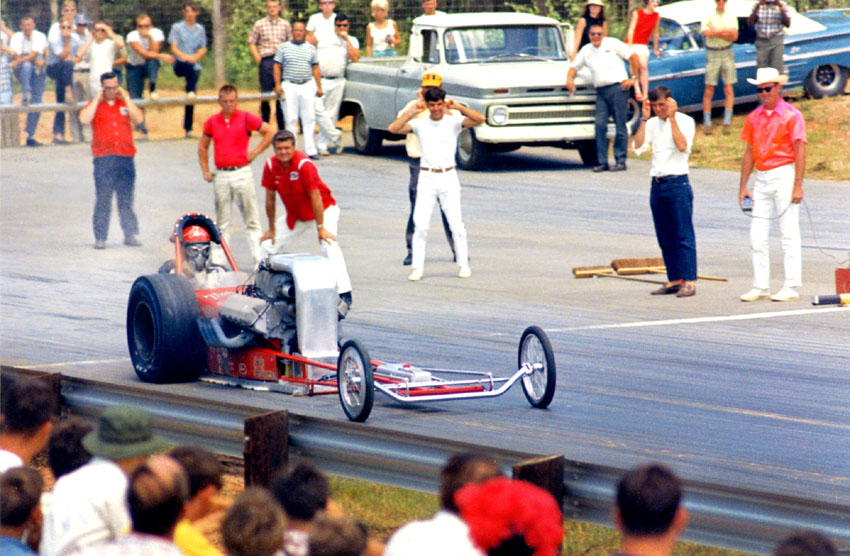

Pete won Top Eliminator at 61 Indy

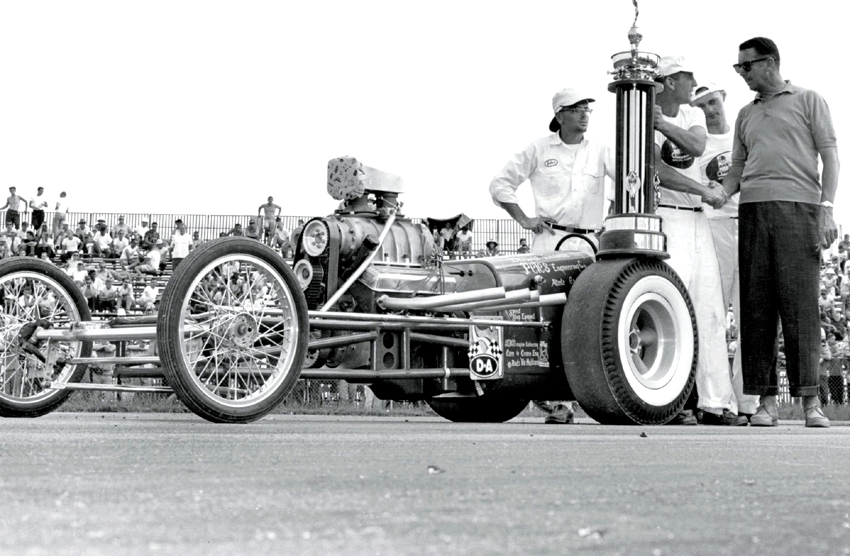

Pete getting his Top Eliminator trophy

Pete with his car

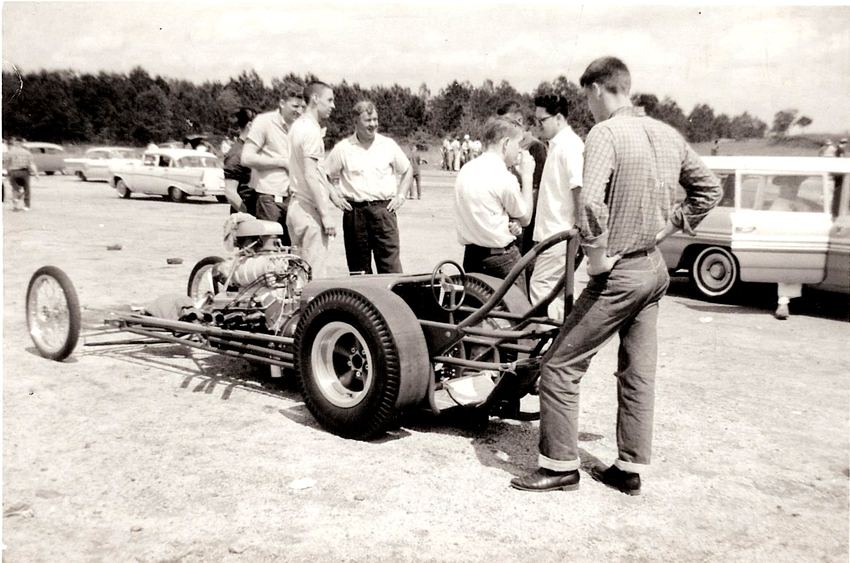

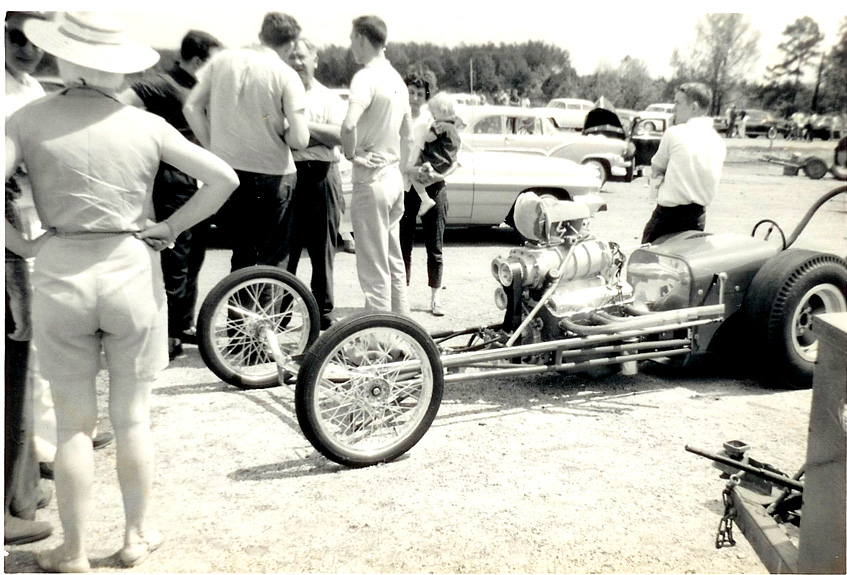

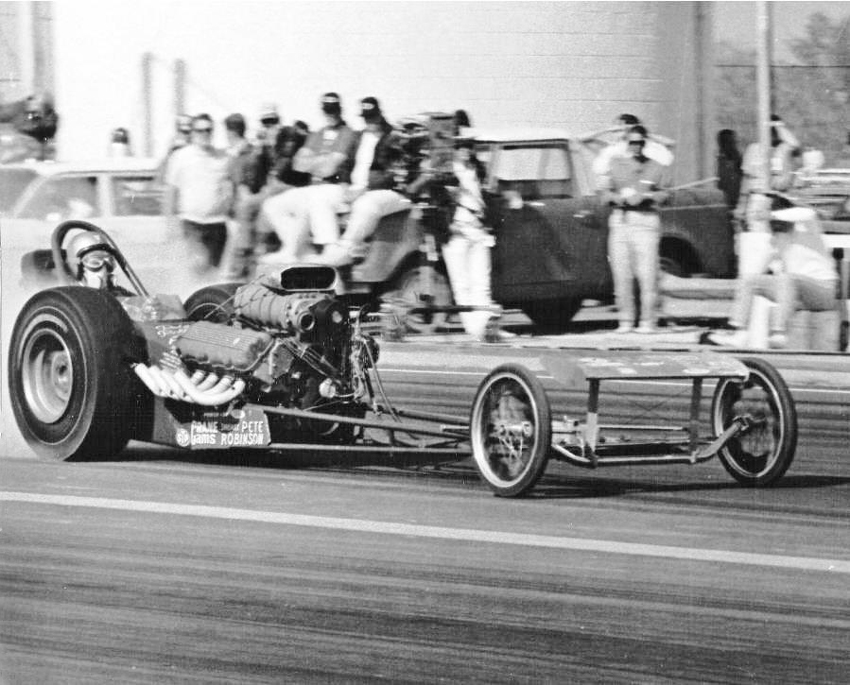

Pete's car draws a crowd

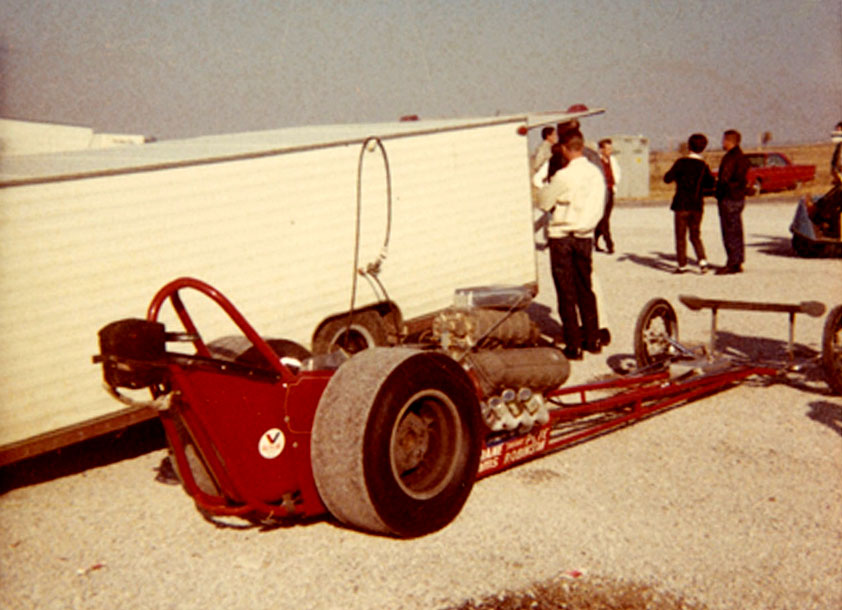

Pete's car

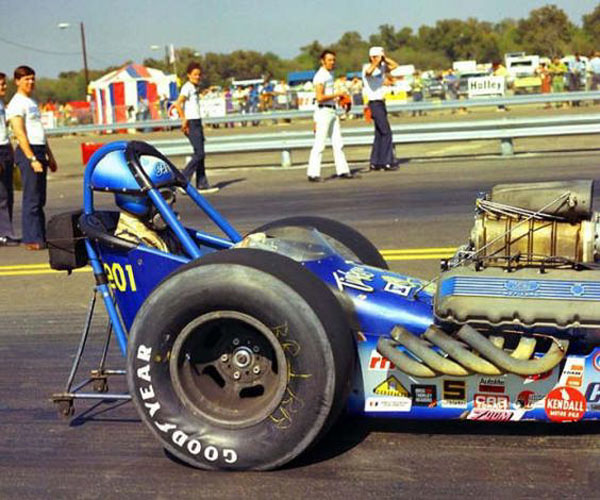

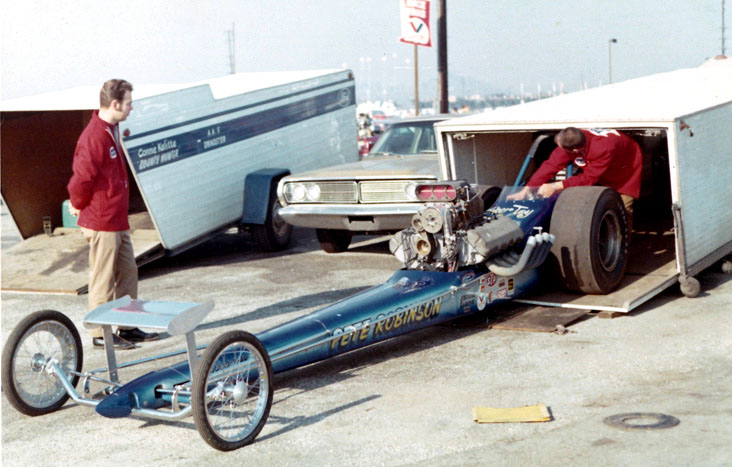

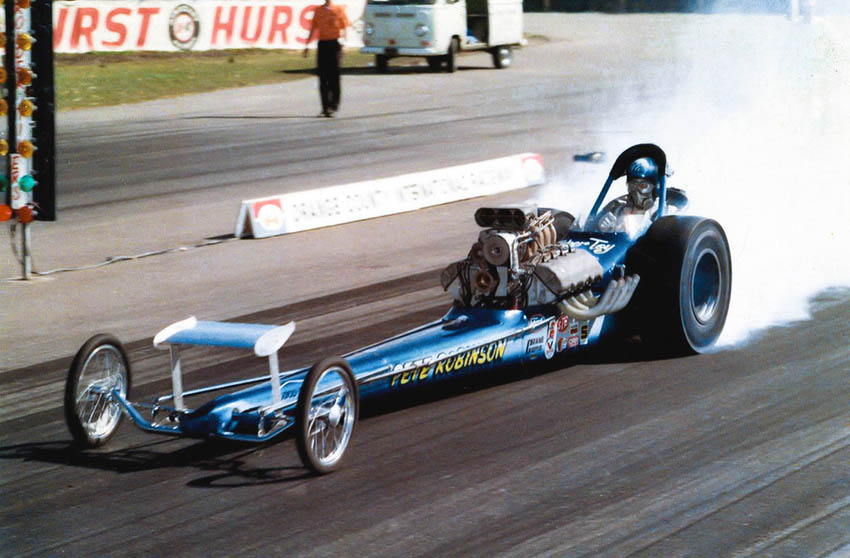

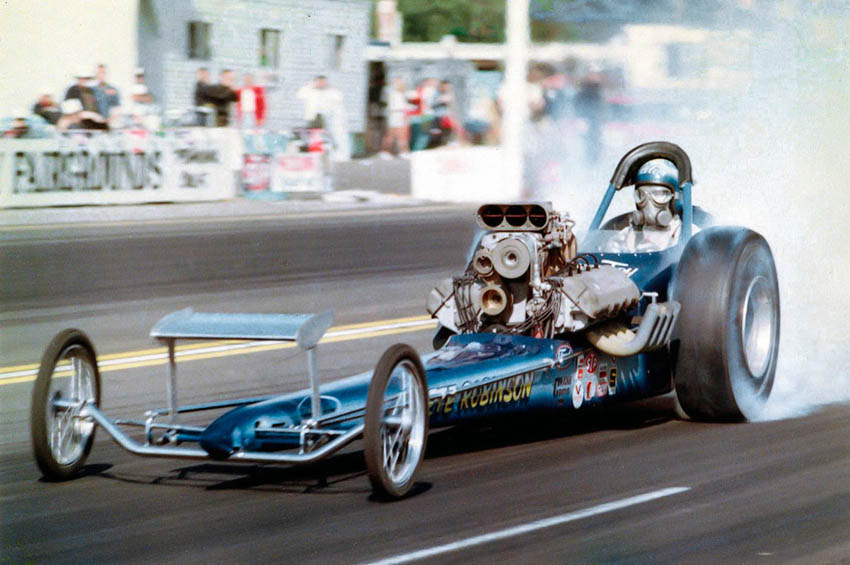

Blue car

Blue car 1966 world finals

Pete

Pete with the vacuum car

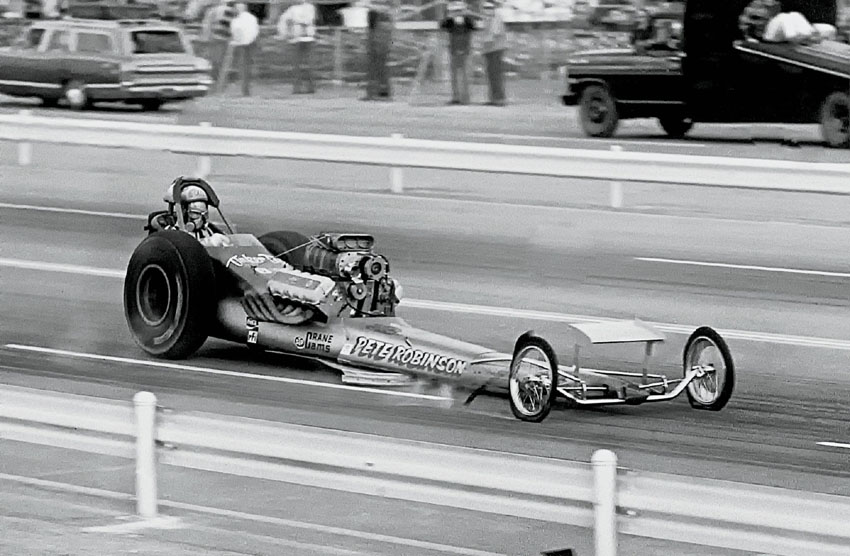

Pete on the gas

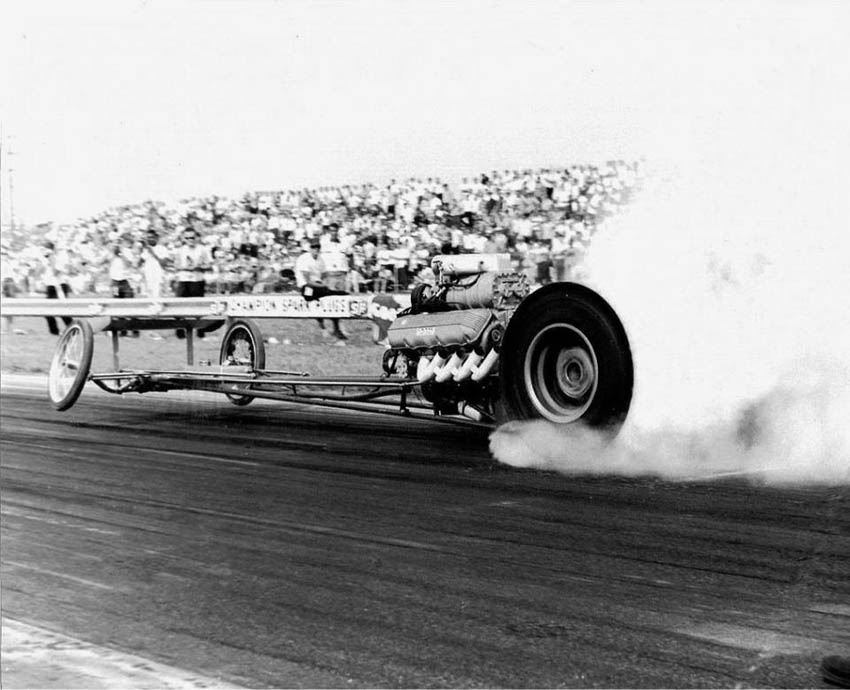

Pete smokin off the line

Pete's lightweight car

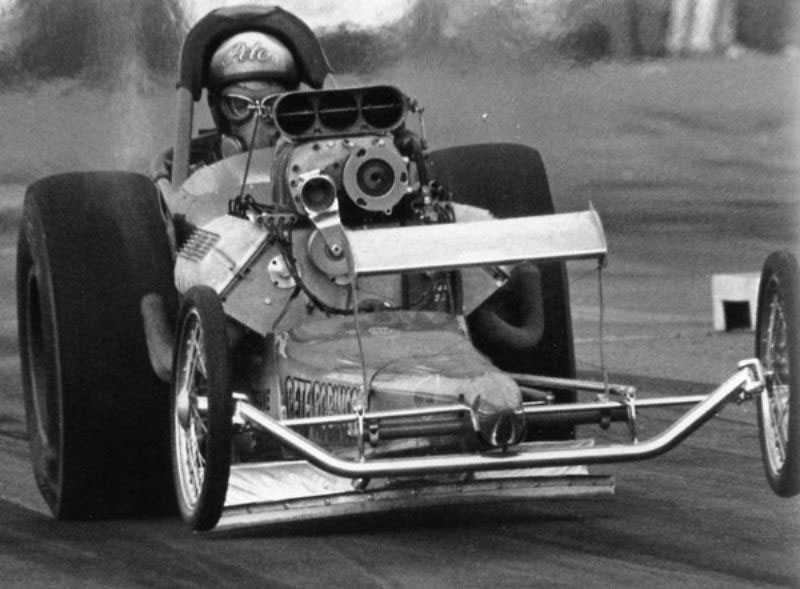

Pete in the car

Pete ready to go

Pete getting the car ready

Pete hooking it up

Pete's ground effects car

Pete taking off

Pete with his car

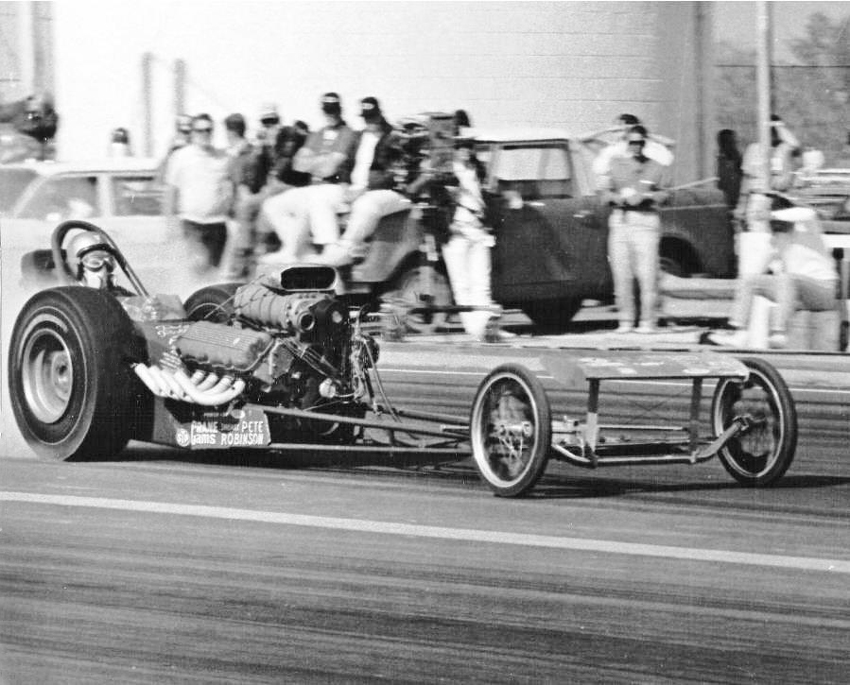

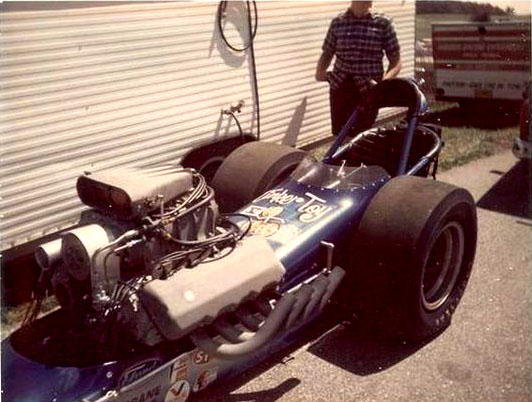

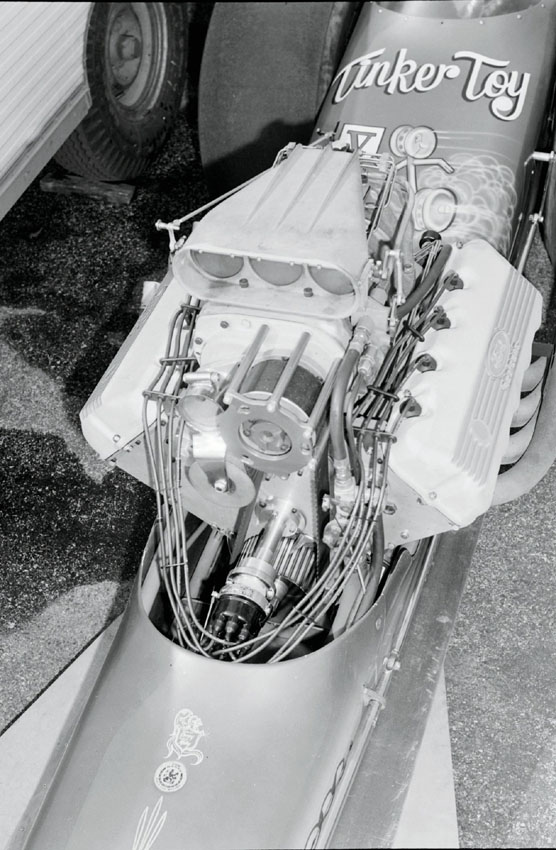

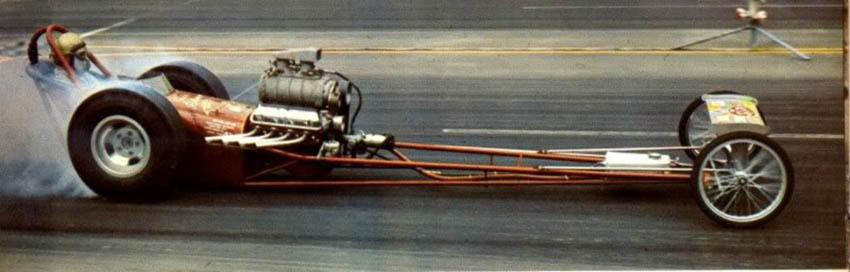

The Tinker Toy

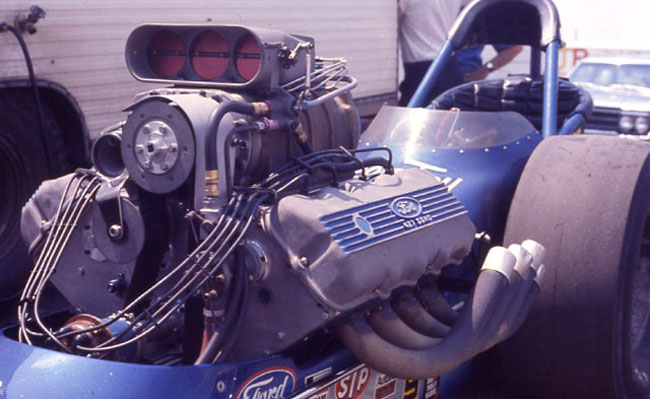

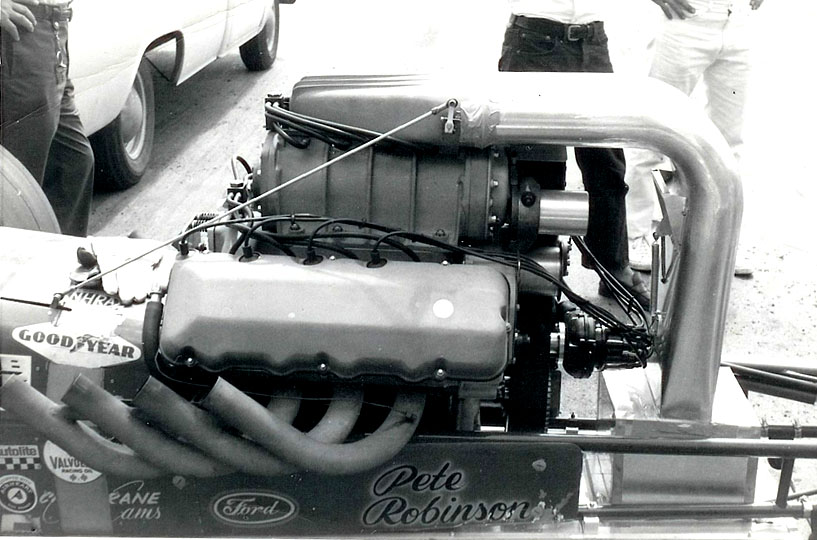

The Ford motor

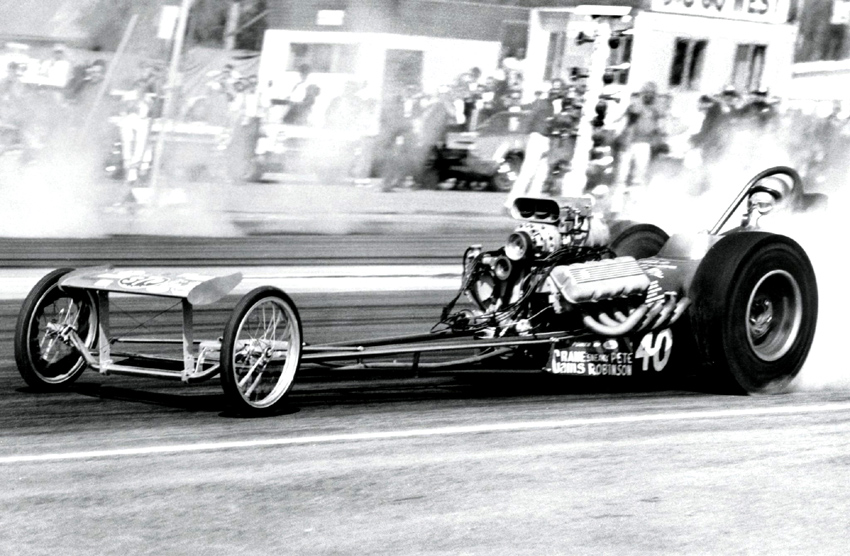

Mean looking car

Tinker Toy

Pete's tires are coming of the front rims

Pete

Pete

Pete

Pete with his vacuum car

Pete's motor

More motor

One more

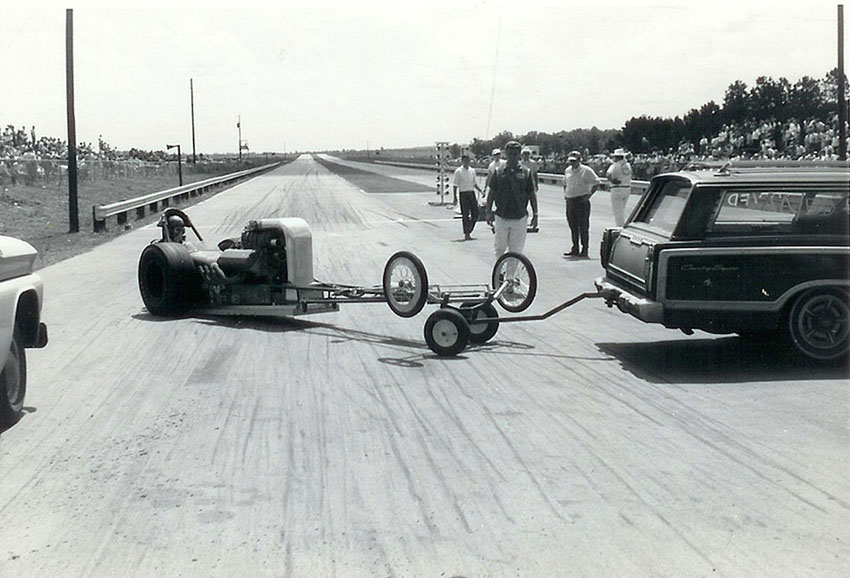

Pete getting a push

Pete's car coming off the small trailer

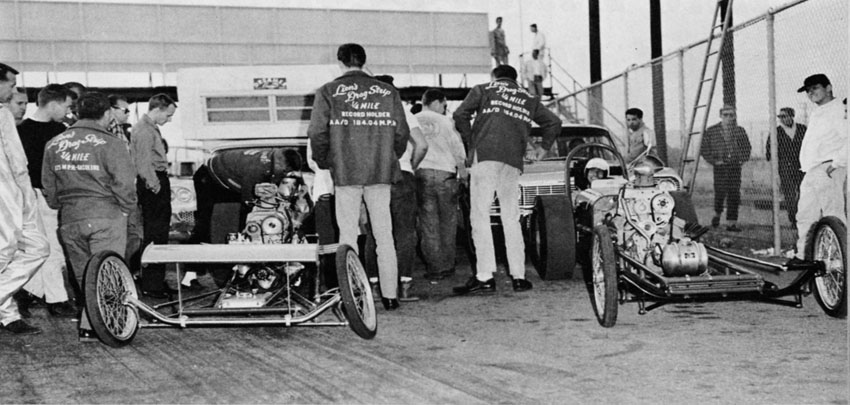

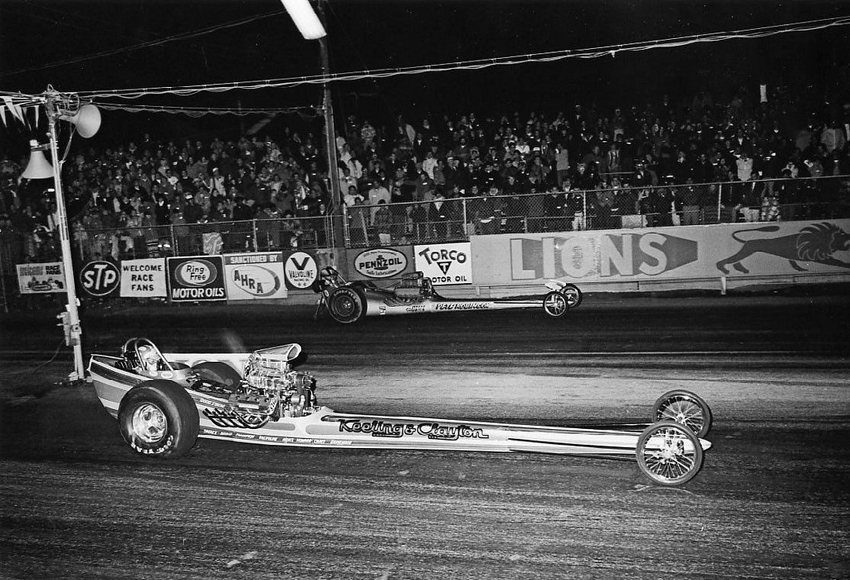

Pete and Danny Ongais at Lions

Pete's little chevy

Pete gets towed back to the pits

Pete smokin'

Pete

Pete

Pete

Pete at Lions

Pete smokin' it

Pete

Pete

Pete

Pete in the Jack car that lasted only one race

Pete smokin' a little Chevy

Pete

Pete

Pete

Pete coming after Tom Hoover 1966

Pete against the Dos palmas car

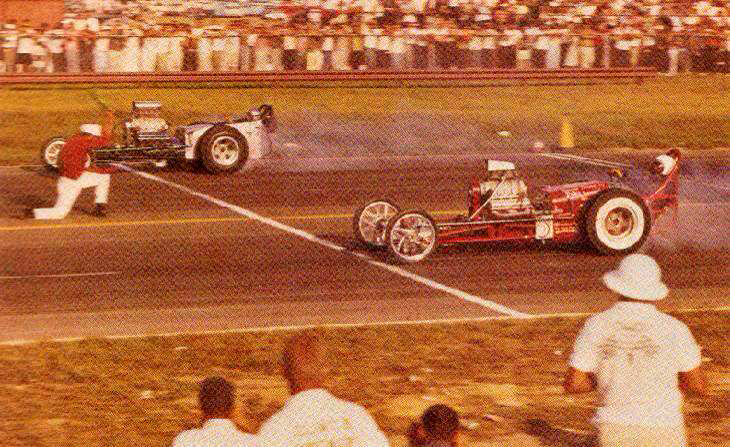

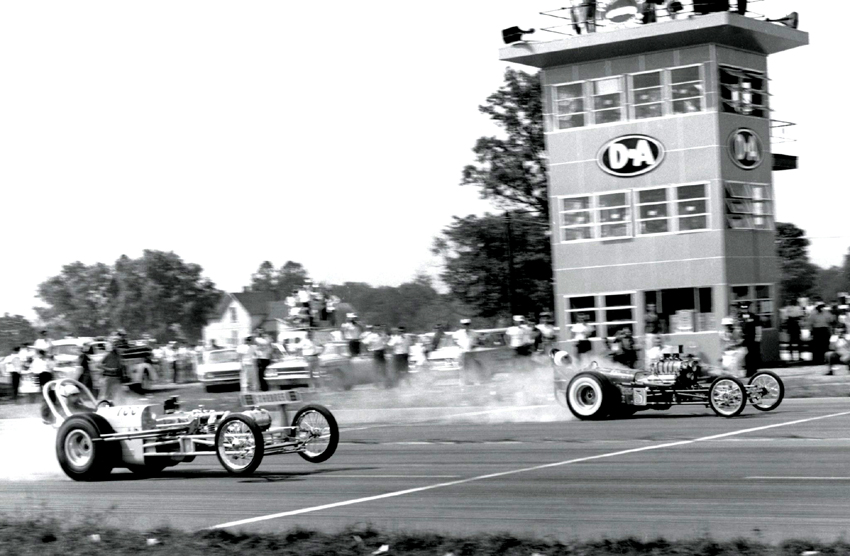

Pete near side at Indy Nationals 1961

Pete on Class Trophy run

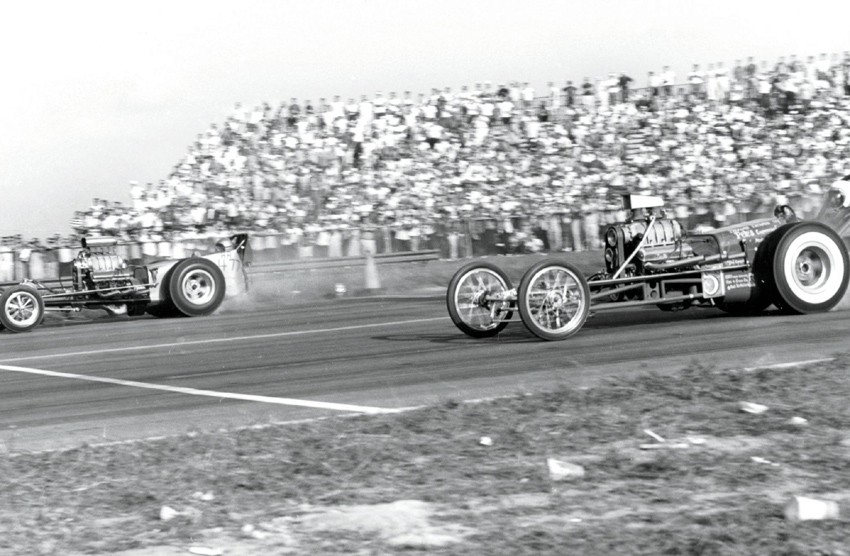

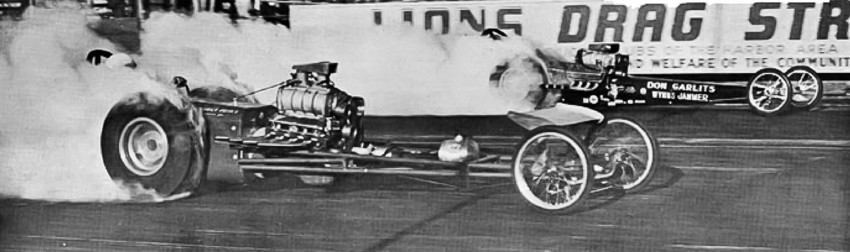

Pete near side against Don Garlits

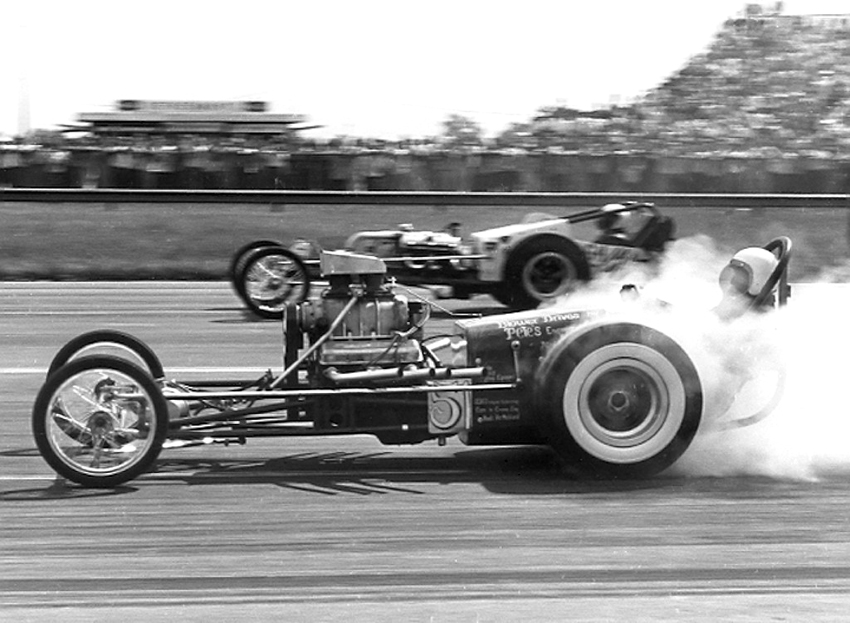

Pete far side against Dean Moon and the Mooneyes car

Same pair

Pete against Don Garlits at Lions

Pete out first here

Pete against Keeling & Clayton

Pete getting at it

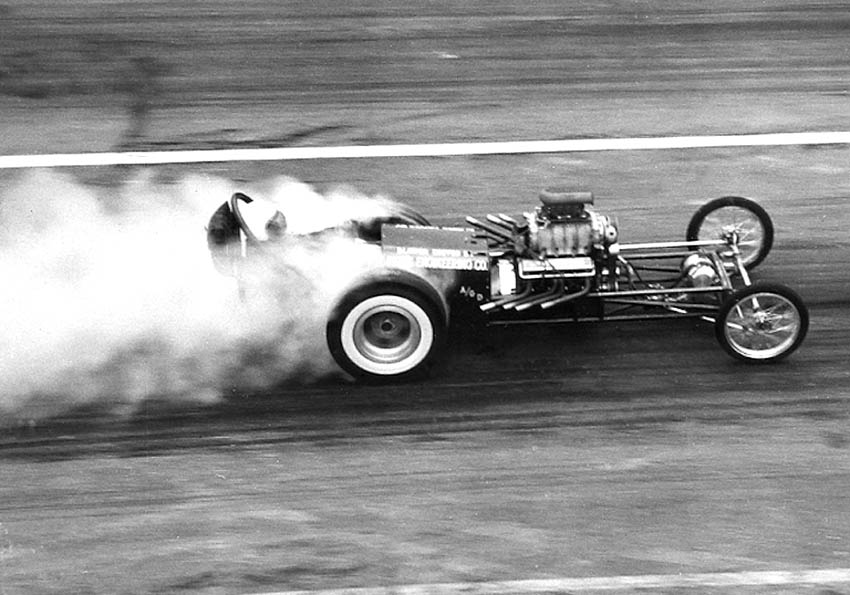

Gassers He started drag racing in 1950, at the wheel of a Buick-engined B/Gas 1940 Ford, which he continued to campaign until 1961. Dragsters

Robinson purchased his first slingshot rail from a wealthy friend, who was unable to persuade his father it was merely a go kart. Robinson, obsessive about lightening his cars (once quipping, "Anything that falls to the ground when you let it go from your hand is way too heavy to be on my race car. immediately began trimming weight off the car, reducing it from 1,256 to 1,120 lb (570 to 508 kg) over the course of three months.He improved its performance from a previous quickest pass of 9.50 seconds to a 9.13.

It was the focus on weight reduction that prompted him to switch to a 289 cu in (4,740 cc) Cobra engine, which was 50 lb (23 kg) lighter than the Chevrolet.

He gained national attention at NHRA's 1961 Nationals at Indianapolis Raceway Park in his small-block Dragmaster-chassied gas dragster, eliminating Tom McEwen (not yet "Mongoose) to win AA/GD before beating Dode Martin to take the Top Eliminator title. Along the way, he set low e.t. of the meet with an 8.68 second pass, which contributed to his "Sneaky Pete" appellation.

At the 1962 NHRA Winternationals, Robinson reached the semi-final in Top Eliminator before being defeated by eventual event winner Nelson.

Robinson also attended the 1963 NHRA U.S. Nationals at IRP.

Top Fuel 1964

Robinson moved up to Top Fuel in 1964. He did compete in Top Gas at the 1964 NHRA U.S. Nationals, losing in the final to Gordon Collett.

1965

Relying on a new 427 cu in (7,000 cc) Ford "Cammer", he reached TF/AD final the 1965 Springnationals at Bristol Motor Speedway, being eliminated by Maynard Rupp. In Top Gas at that event, he lost to Collett again.

1966

He started his 1966 Top Fuel season at the AHRA Winter Nationals at Irwindale Dragway in Irwindale, California. He was eliminated in the second round at Pomona by Mike Snively (driving for Roland Leong). He was eliminated in round one at Bristol. At the NASCAR Summer Nationals, held at Dragway 42 in West Salem, Ohio, he qualified #2, and defeated Joe Jacono (#10 qualifier) in round 1, Chris "The Greek" Karamesines (#14 qualifier) in round two, and #16 qualifier Connie Kalitta in the semi-final, before losing in the final to #1 qualifier Nick Marshall. At the Nationals, he lost in round one to Nick Marshall.

He took his first Top Fuel win just over a month later, at the World Finals, at Tulsa Raceway Park in Tulsa, Oklahoma. He eliminated Kalitta in round one and Wayne Burt in the semi-final, before defeating Dave Beebe in the final with a 7.17 second pass.

1967

Robinson started the 1967 season with a victory over Jerry "King" Ruth, but a loss in the semi-final to Kalitta, at Pomona.

He suffered a broken arm in tire testing early in the year, but still made it to the TF/D final of the 1967 Springnationals at Bristol, eliminating Tom Hoover in round one and Leroy Goldstein ("the Israeli Rocket") in the semi-final, before being beaten in the final by Don "The Snake" Prudhomme. During the 1967 season, he also tied McEwen's record 6.92 second pass.

1968

Beeline Dragway in Scottsdale, Arizona hosted the AHRA Winter Nationals to start the 1968 season. With the field including Tom Hoover, Frank Pedgregon, Leroy Goldstein, Danny Ongais, Tom "Mongoose" McEwen, and Chris "The Greek" Karamesines, Robinson again lost to Prudhomme in the final. At a match race at OCIR in March, Robinson joined Larry Dixon, Prudhomme, Kalitta, McEwen, and Don "Big Daddy" Garlits; Garlits would ultimately be beaten in the final by Vic Brown. At the Springnatls at Englishtown, again facing the likes of Karamesines, Prudhomme, Kalitta, and Garlits, Robinson failed to qualify.

1969

Opening the 1969 season, Robinson returned to Beeline, qualifying #30 for the AHRA Winter Nationals, in a field that included Goldstein (the eventual winner), Hoover, Karamesines, Prudhomme, Kalitta, and Dixon. The AHRA Spring Nationals featured a field of sixteen, again hosting Goldstein (once more the eventual winner), Karamesines, and Prudhomme; Robinson qualified #15. At the NHRA Nationals, he was eliminated in round one by eventual winner Prudhomme. The event was marred by John "The Zookeeper" Mulligan's wreck; Mulligan died of his burns sixteen days later.

1970

The 1970 AHRA Winter Nationals saw Robinson qualify #14 in a field of 16, only to lose in round one to #3 qualifier John Wiebe; the early loss earned Robinson US$200. Robinson won TF/D at the Summernationals, at York U.S. 30 Dragway in Thomasville, Pennsylvania, by beating Jim Nicoll in the final. It earned him US$7250. Later that year, he won the 1970 AHRA World Championship at Bristol, beating Jimmy King in the final. Before the year ended, he went back to IRP for the 1970 NHRA Nationals, eliminating Chip Woodall in round 1 and Bob Murray in round two before losing in round three to Prudhomme. Robinson attended the 1970 NHRA World Finals at DIMS, in Lewisville, Texas; it was won by Ronnie Martin.[43] Robinson went back to Beeline for the 1970 AHRA Winter Nationals, but failed to make the field.

Following his successful 1970 season, now being the only driver left running a 427 Cammer, and having lost factory support, Robinson decided to retire and concentrate on building lightweight casings for superchargers, differentials, and similar components. He hired Bud Dabler to drive his new ground effect-equipped dragster, instead. Dabler disliked the car.

1971

Entering at Lions for a 1971 AHRA TF/D event, Robinson was eliminated in round one by Rick Ramsey, which paid just US$200. At the first ANRA Grand American Series event of the 1971 season, Robinson clocked the quickest pass of his career, a 6.50, in the new car, and decided to enter at the 1971 Winternats, only three weeks away. At Pomona on 6 February, he qualified with a 6.77, low e.t. of the day. On a subsequent pass, the chassis twisted, causing the front tires to separate from the rims; Robinson, in the right lane, hit the guardrail, and the car broke in pieces.

Death and legacy

He was taken to hospital in Pomona and died later that day. He was thirty-seven.

At his death, Robinson was "one of the sport's best-liked gentlemen". Don Garlits, himself an innovator, respected Robinson's engineering: "Pete was always on the edge of the envelope..."

He would be listed #22 on NHRA.'s list of its Top 50 Greatest Driver

Drag-Racing Innovator and Champion

The long, blue dragster moved slowly toward the starting line. Pete Robinson was carefully lining up his race car for what would be his last chance to qualify for the 1971 NHRA Winternationals. Getting a spot in the 16-car field was critical. He was far from desperate, but he had no sponsor and was racing out of his own pocket.

But his car had it all: a new chassis built by pipe master Woody Gilmore and a hand-formed, full-length aluminum body crafted by metal wizard Tom Hanna. Compared to the field, the car’s engine was an oddity—not a Hemi of some stripe—but a Ford 427 SOHC. Pete had long felt that the SOHC configuration was better suited to nitro racing than a pushrod design, and he especially preferred the engine’s ability to safely rev considerably higher.

The blue car had Bud Dabler listed as its driver. However, Robinson decided at the last minute to drive it himself. Pete’s decision was not made on a whim. Twice before he had suffered serious injuries driving the perilous slingshots and felt he could better advance his racing program by spending his time outside the race car. He needed to qualify it for both monetary gain and to prove the validity of his latest ground-effects system.

At the green, Pete’s car left the line swiftly, clutch dust billowing, engine thundering. At mid-track the ground-effects device, an undercar skirt designed to create a negative force, was working well. The car seemed glued to the surface like a lizard on a pane of glass.

Gaining speed rapidly, Pete entered the second half of the quarter-mile when something went dreadfully wrong. Photos by acclaimed veteran Jere Alhadeff show the steering rod bowing and the tie rods severely flexed and that both front tires were separating from their motorcycle rims. Pete had the butterfly steering wheel turned hard left, all his focus on trying to avoid the guardrail. Pete’s helmet is also raised far up on his forehead, suggesting that it was coming off. This was not all that unusual, and many drivers were photographed at 220-plus with helmets high on their foreheads from the extreme turbulence.

A microsecond after Alhadeff’s shocking photo, Pete’s car slammed into the Armco. As the car disintegrated on the cruel steel rail, a huge dust cloud spewed upward, and parts large and small showered the area.

Emergency workers, NHRA officials, and nearby racers rushed to him. The rollcage had done its job, and Pete was somehow still alive. He was rushed to a hospital, but soon after, Pete Robinson was dead. He was 37 years old. His survivors include his wife, Sandra, and daughter, Kelly.

The remains of Pete’s car were collected, examined by NHRA officials, and then released to his family. Pete’s Country Squire push car and trailer were said to have been driven home to Atlanta, possibly by Bud Dabler or Pete’s brother, Torch Robinson, but it’s not known if this actually happened.

Lew Russell Robinson was born in Atlanta on June 2, 1933. He attended classes at the Georgia Institute of Technology (Georgia Tech), a university known for engineering and mathematics, but Tech graduation records do not list a Lew Robinson. Still, his time there ingrained in him engineering principles and use of the scientific method for problem solving, skills that he quickly applied to straight-line-acceleration motorsports.

Along the way, he acquired the nickname Pete, which seemed to fit his low-key, always-affable personality. His first hot rod was a 1940 Ford coupe powered by a Buick nailhead enhanced by a 6-71 blower and drive system that Pete designed and built. The Buick also had a flat-tappet camshaft from little-known Florida cam grinder Harvey Crane. Pete’s satisfaction with the cam established a friendship that endured throughout his career.

After some street racing, Pete began running his ’40 at area dragstrips. In 1959 and 1960, he towed it to Detroit to the NHRA Nationals, but had little success. Wanting to go faster, in 1960 he sold his beloved ’40 and placed an order for a dragster chassis from Dragmaster Company in Carlsbad, California. He also acquired a partner, friend Bill Word, who spent most waking hours as an antique furniture refinisher. Jim Nelson and Dode Martin had been building sturdy, efficient, good-handling dragster rails for a couple of years, their reputation bolstered by the safety-conscious NHRA’s unofficial endorsement of the Dragmaster chassis for its design and construction.

For power, Pete and Bill chose a 283 Chevy that was bored 0.125-inch oversize to 4.00-inch. A half-inch stroker crank (3.52-inch) increased displacement to 354 ci. They completed that project with a supercharger. Pete built his own drive system, at the same time establishing Pete’s Engineering Blower Drives, to manufacture and sell kits for the Chevy. The assemblies featured precision machined-aluminum components and sold for an attractive $249.

Thus equipped, Pete and Word headed for the 1961 NHRA Southeast Division event at Covington, Georgia, and surprised everyone by winning Top Eliminator. Other wins followed, highlighted by 8-second, 170-mph performances.

In late summer, Pete filed an entry for the NHRA Nationals at newly completed Indianapolis Raceway Park. After holding the Nationals in Kansas, Oklahoma, and Detroit, IRP was touted as a surefire place to set records. Pete’s presence went unnoticed. His anonymity lasted only until his first time trial when he clicked off a mid-8-second elapsed time.

In 1961, NHRA rules stipulated pure pump gasoline, as per the fuel ban (1959–1964). Consequently, to gain performance, many of the top teams had gone to twin engines. Classified as AA/Dragsters, these cars generally overpowered the tires, but the big twins made up ground with a huge top-end charge. Although classified as an AA/D, Pete’s car spotted the twins as many as 400 ci, but at just 1,250 pounds, it weighed 600 to 800 pounds less than the two-motor monsters.

Pete defeated all comers to take Sunday’s AA/D class trophy. In the final, the unheralded Robinson ran against young Tom McEwen, who was driving the heavily favored Adams & McEwen–blown, Oldsmobile-powered AA/D, owned and tuned by Hilborn’s Gene Adams. Pete’s Southwind lifted its front wheels and blasted ahead of McEwen, taking the trophy with an 8.86 at 170.77 mph. Unheralded and still largely ignored, the soft-spoken Georgian had defeated the nation’s fastest and quickest single- and twin-engine dragsters.

The format in those days had the AA/Dragster winner facing off against the winners of A/Dragster, A/Modified Roadster, and A/Competition Coupe for overall Top Eliminator trophy. The little blown Chevy performed flawlessly, and Robinson became the 1961 NHRA Nationals Top Eliminator Champion by defeating Bob Carroll’s blown Hemi-powered A/Competition Coupe.

At that race, some competitors cried foul on Pete’s external water-injection system. He explained that his engine used a higher compression ratio than was common and the homemade water injection merely protected it from detonation, but he removed the device without argument. Sans the water injection, he proceeded to go even quicker, recording stunning elapsed times of 8.46, 8.52, and 8.62—all of them nudging the 170-mph mark. The next week at Detroit Dragway, he ran 8.79 at 170.45, setting track records in the process. Though the big-twin cars were nearly 10 mph faster, Pete’s lightweight Chevy was engineered to get there first.

During his early engine build-up, he had Harvey Crane design a roller cam for his engine. Thus, Pete’s Indy win propelled Crane’s mom-and-pop cam shop to instant national prominence, and Harvey always credited Pete’s win as the company’s turning point.

“As soon as Pete Robinson won the Nationals, my phone started ringing with calls from all over the country. I was more surprised at the number of calls I got from California, something that had never happened before. Pete also ran my first roller tappets and aluminum rocker arms, which made my company credible with racers. Pete was always totally honest, and he was the first racer I ever paid. Pete got a check from me for $150 every month. We made the deal on just a handshake,” Harvey related in a conversation shortly before his death on May 31, 2013.

After Indy, Pete sold his Dragmaster and ordered the newer Dragmaster Dart-style chassis. It was a little longer and the framerails tapered down at the front. Pete’s new Dart conformed to his obsession for extreme weight savings. Although he never scrimped on unsafe materials, he was fanatical about eliminating weight not directly related to safety or performance.

Pete was known to spend hours grinding to remove excessive flashing, snots, and unnecessary bosses. Anything that failed to contribute to performance was excised, and this included his personal attire. Before a run, Pete headed to his trailer and removed all his clothes, save for his skivvies, and donned his driver suit and lightweight, well-worn sneakers. The weight savings amounted to just a few pounds, but he said it made him fit more securely in the seat. He abandoned the small-block Chevy for the lighter Ford 289-302, stroked to 354 ci. Equipped with his magnesium components, the Ford-powered version weighed less than 1,000 pounds.

His obsession often put him in trouble with tech officials. He insisted that a race car have adequate braking for the speeds reached. Rules stated that any car exceeding 150 mph must have a drag chute. After being told to install one or be denied entry, he countered with a miniature, lightweight rendition, as the rules did not specify size. He continued to use the brakes for stopping and released the chute only when an inspector asked for a function check. This was but one of the stories that formed the legend of “Sneaky Pete” Robinson.

Pete’s engineering mind worked without respite. When drag racing became enamored with big mph, Pete countered by correctly stating that e.t. won races and that extreme speed was dangerous. His engines always used the finest lightweight components, built for maximum rpm levels that most builders avoided. Using deep gearing to reduce elapsed time was Pete’s creed, and many of his lowest times arrived with a head-scratching lack of top-end speed.

Pete envisioned the rear wheels of his race car as flywheels capable of storing enormous amounts of energy—energy that’s only available after the car is moving and the laws of physics can be utilized. To gain an edge, he built a jackstand arrangement that raised the rear of the car off the ground after it had been staged and was ready to run. At a given rpm, he released the clutch and brought the engine speed up to a certain point. On the green, he dropped the car off the jackstands, floored the throttle, and the car shot off the line.

Pete used the jacks several times in match races and even tried them once at the NHRA Nationals in 1962. On his first and only run with this system, the tires began to grow slightly due to centrifugal force. Smoke boiled off the rear tires while the car sat motionless. The NHRA’s revered announcer, the late Bernie Partridge, was dumbstruck. He blurted: “His tires are smoking and the car’s just sitting there!”

No one knew just how quick Pete’s “jack-assed” run had been. The NHRA refused to announce his elapsed time and speed. Pete had barely cleared the traps and pulled onto the IRP return road when Partridge announced: “Would Pete Robinson please report to Ed Eaton, immediately!”

Eaton was the NHRA Eastern Division honcho and event director for the Nationals. Pete protested that the system was perfectly safe, the car ran straight as an arrow, and that it was rules-legal. Uncle Ed thought otherwise and informed Pete that as of that minute the NHRA rules had changed and he promptly banned its use—forever. It was yet another chapter in the growing Sneaky Pete dossier.

After his Nationals victory, he continued to score wins at major races. These included: the 1962 California Gas Championships and 1962 World Series Top Eliminator; 1964 Bakersfield No. 1 Eliminator; UDRA’s first national event, at Lions Drag Strip in 1964, where he recorded an amazing 8.14-second e.t. record; the 1964 NHRA Nationals AA/Dragster class winner; Bakersfield Top Gas Eliminator; and AA/D class winner at the inaugural NHRA Springnationals at Bristol Dragway in 1965.

Although he scored numerous Top Gas Eliminator titles, the tide of drag racing had turned away from gasoline-fueled dragsters, specifically at the Nationals. As early as 1962, the NHRA had run Top Fuel for the West Coast fans and racers at the Winternationals. In 1964, they brought big-time nitro racing back to Indy, which proved to be a huge success with nearly 50 Top Fuel entries on the Garvin family’s property at IRP. Pete knew that to advance his career he needed to move to exotic fuel.

This he did with assistance from Ford Motor Company executive Al Turner, who was instrumental in signing top names willing to run the new SOHC 427. Pete’s switch from Chevy to small-block Ford in his gas days had not gone unnoticed. He immediately ordered a new Woody chassis and began preparing a SOHC for Top Fuel.

With the new engine came reliability issues, due mainly to oiling-system inadequacies. The ‘Cammer main and rod bearings were prone to failure with nitro-diluted oil. An aftermarket fix from Don Alderson’s Milodon Engineering resolved the crisis with a system that featured a specially designed, high-capacity, baffled oil pan with large, high-volume, braided steel lines and a high-volume, high-pressure pump.

Late in 1965, Pete collected Top Fuel honors at the 1965 Atlanta $10,000 event and followed with a win at the 1966 NHRA World Finals, setting the AA/FD elapsed-time record at 7.17 seconds.

He scored again in 1967 at the High Altitude Nationals in Denver. In between his 1967 win and 1970, he remained competitive, even during a nasty crash during a tire test. Pete’s arm came out of the car and required surgery and rehabilitation to restore its function and strength. That inspired him to create currently required dragster arm restraints, to keep hands and arms inside the car in a crash.

At the 1967 Springnationals in Bristol, Pete showed up with another innovation. He never liked the idea of push-starting, claiming it was both hazardous and time consuming. His fix was a system that used compressed air in welding bottles to power an aircraft starter. His system avoided push-start accidents and provided the advantage of having a crewman ready to tighten a loose fuel line or fitting, thus saving a run or preventing a shut-off-on-the-line order during eliminations. His self-starting system was eventually made mandatory by the NHRA, AHRA, and IHRA.

The year 1967 also heralded the era of the slipper clutch, and the extreme tire shake that came with it—oscillations violent enough to knock a driver unconscious. The NHRA rules required “padding” for the rollcage, but this did little to protect the driver’s head. Pete experienced several incidents where his helmet was pounded into the rollcage, causing the helmet shell to fracture and giving him a concussion.

His solution was a sort of a hemisphere that accommodated the helmet secured within the rollcage. For shock absorption, the “brain bucket” was made from the same liner material used in helmets. Bell, the leading helmet maker of the day, provided the liner material and built the bucket to Pete’s specifications.

In his quest for the lightest weight, Pete collaborated with Gasser icon and ‘Cammer user George Montgomery, who had the resources for precision magnesium casting as well as machining. The collaboration resulted in numerous components for the SOHC and especially the supercharger cases. Today these “Pete’s-Montgomery” components are highly prized.

For some time, Pete had theorized that quicker e.t.s required utilizing more of the overly abundant power produced by nitro-fueled engines. Tire technology had advanced tremendously and controlled-slippage clutches made the cars quicker, but still wasted available power, especially from mid-track on, where the big fuel-burners produced maximum torque. Pete’s idea was to utilize the air beneath the race car to stick it to the track surface.

His first design was a device that ducted the intake area of the Enderle Bug Catcher injector beneath the car. The low pressure created by the supercharger would be enhanced by air under the car, creating an extreme low-pressure zone and resultant increase in traction. Pete fabricated his “Vacuum Cleaner” system and took the car to the NHRA Division 2 points meet at Warner Robins, Georgia, in July 1968. He chose not to enter competition and instead just make a couple check-out runs to test his ground effects.

His first run was a half-track squirt. He shut-off early. He returned to the pits and found surface debris, sand, pebbles, and bits of tire had been sucked up into the engine. He scrapped his original idea and developed a much simpler design in a rubber-skirt undercar device that trapped onrushing air and created a suction-like downforce. This device was on the car at the 1971 Winternationals, and many cite it as the cause of Pete’s fatal crash.

In 1968 he began to experience catastrophic blower explosions, boomers that were costly and dangerous. He theorized that the lengthy drivechain for the SOHC’s twin camshafts was experiencing “clearance stack” under load, thus stretching the chain and retarding cam timing. To prove this, he loaded his race car in the trailer and drove south to Hallandale, Florida, to see old friend and sponsor Harvey Crane. On Harvey’s engine dynamometer, Pete rigged up degree wheels on the front of each camshaft, and then set up an 8mm home movie camera and a strobe timing light to record the action with the engine running. Cobbled up with duct tape and well wishes, Pete fired the Ford.

The instant the nitro-guzzling engine fired, it was so loud and startling that everyone in the Crane shop guessed “explosion” and ran for the doors. Unfazed, Pete hand-throttled the big motor up to a lazy 5,000 rpm and shut it down. After normal engine maintenance and checks, he moved the camera and repeated the exercise. When the film came back, he found that his theory was correct.

To replace the cumbersome SOHC chaindrive, Pete designed and machined a series of gears and a front cover. He utilized the new gear drive to capture the 1970 AHRA Grand American Series Top Fuel Eliminator in August at Bristol. He also took the NHRA Summernationals at Englishtown that same year.

Pete began the 1971 season by towing west for the early winter events. Three weeks before Pomona, he clocked a 6.50—his best elapsed time—at the AHRA Grand American Series race. He remained on the West Coast and then entered the 1971 NHRA Winternationals. Pete’s new driver, Bud Dabler, yielded the seat to Pete. Dabler’s discomfort was with the new ground-effects system.

Did Pete’s innovation cause the accident? Perhaps. But another theory has it that a rear-axle component broke during the run, forcing the car into the guardrail. Alhadeff’s graphic last-run photo shows Pete with the steering wheel turned nearly vertical, desperately trying to move the car left. This may have been a response to a major driveline failure—or maybe extreme oversteer created by the ground-effects system. More than 40 years have passed, and this question remains unanswered.

Many of Pete’s safety advancements remain with us as his legacy. His legend was preserved with his induction first into the NHRA Southeast Division Hall of Fame in 1983 and the International Drag Racing Hall of Fame in 1992. In 2001, during its 50th anniversary, NHRA named a panel of The 50 Top NHRA Drivers of All Time. Pete Robinson was number 22 on that elite roster.

Don Garlits was quoted in National Dragster: “If he had survived that horrible wreck, he’d be an engineer on some team right now. Pete was always on the edge of the envelope, and I always had respect for him. Pete just didn’t stick somebody in the car when he had some idea. He was the test pilot, just like Chuck Yeager or any of them. He took the risk, and there’s a lot to be said for that, too.”

NHRA founder, the late Wally Parks, said in that same issue: “Who can guess what his fundamental talents might have contributed in today’s world. Pete was an innovator whose discoveries were the leading edge of technology.”

Pete Robinson earned his nickname. One of his sneakier innovations was a starting-line launch system that he introduced on his second Dragmaster chassis, the Dart car he ran in 1962.

He preferred a locked rear axle, with the spider gears immobilized (accomplishing the same thing that a modern spool does). The locked axle made his jack system possible because both tires would spin at a constant and equal speed, like giant gyroscopes, storing energy produced by centrifugal force. Since his small-block Chevy had a much narrower peak-torque band than did the popular 392 Hemi, the jacks enabled him to be able to get his Chevy at peak torque output—and literally squirt off the line when he dropped the car down.

This also reduced shock load at launch, saving driveline components. Pete favored a 1955–1957 Chevy axle over the heavier Olds-Pontiac units. Though the Chevy rears were weaker, they were quite up to the task in an ultralight car such as his. He further lightened the load by manufacturing a cast-magnesium centersection that used shortened and re-splined Chevy axles (forged and billet aftermarket shafts were still decades away).

He also utilized a single rear disc brake, again feasible due to his car’s extreme light weight. How he managed to sneak one brake past the tech inspectors is unknown, but he ran that system for several years.

Another even more important benefit was a quicker starting-line reaction to go along with the psychological edge. When his little car shot off the line, the opposing driver would often bury his foot even deeper, boiling away rubber and precious milliseconds as the Sneaky Pete Special scooted to the finish line.

Pete’s lightweight obsession carried over to the jack system. It was comprised of equal-length jack ends that he raised mechanically with compound leverage. Release came via a single cockpit lever. With the car stationary, both tires billowing smoke and the engine singing high-C resulted in a lightning-like launch.

Critics claimed that his innovation was unsafe as well as unfair, and one of the most vocal was Don Garlits. Garlits had gotten a close-up of the system when the upstart Georgia boy used his jacks to take a match-race win from Don’s big-inch Hemi. Wherever Pete used the system, witnesses reported the car always ran string-straight with zero handling issues. But his curiosity soon became a moot point. The NHRA technical director, Bill Dismuke, and Nationals event director, Ed Eaton, outlawed the jacks at the 1962 Nationals, immediately after Pete had made a single jack-assisted pass. Soon after the car cleared the traps, the bureaucracy lashed out. The NHRA rulebook was amended on the spot, requiring the rear tires to maintain constant contact with the track surface.

Robinson’s elapsed time that day was not mentioned on the PA system, either, but the instant controversy meant he likely ran a very low-8- or possibly high-7-second elapsed time—performance that was unheard of for a gas-burning dragster in 1962. Pete didn’t win the Nationals that year, but his remarkable performance enhanced the growing legend of Sneaky Pete.

Pete Robinson's "jack car" was his second Dragmaster chassis, one of the slightly longer wheelbase "Dart" style chassis. He did run against fuelers in match races and won more than a few of these, especially on the sorry-surface tracks that were typical for most of the East Coast back then. High HP Chryslers, on nitro, just freewheeled while Pete's little Chevy car was headed for the finish line traps.

Pete took his jack deal to Indy, for the Nationals. He pulled to the starting line, lifted the car up and lets out the clutch. Tires start spinning and grow, enough so that they begin to smoke WHILE THE CAR IS SITTING STILL, THERE ON THE LINE!

The starter, the car in the other lane, the announcer (Bernie Partridge), Event Director Jack Hart and everyone starts to freak-out. Finally the flagman throws the green and Pete's little car zips out and is gone. It hardly got stopped at the other end before the PA system is calling: "Pete Robinson report to the D-A Tower immediately!"

Uncle Jack Hart told Pete to lose the jacks - forever - or hit the road.

Pete's penchant for thinking his way quicker and faster told him that the spinning tires would act like a pair of big flywheels propelling the car's mass and weight almost instantly, and dropping his ET. Pete was never concerned with speed; MPH numbers to him were irrelevant to the concept of drag racing, which was to get to the finish line FIRST. NHRA wasn't ready for such a quantum leap in the physical limitations of dragster technology and immediately banned such antics, forever.

It's not hard to understand NHRA's position, especially when it was sprung on them in such an off-the-wall typical Pete fashion. But then, Pete never really could understand how the entire world couldn't embrace his technological ideas and move forward at the same speed which Pete's mind was running.

Pete saw drag racing as his own Physics Lab, one giant experiment that was rewarding from an R&D sense, and a lot of fun in the process. He was also highly safety conscious. He was the first to develop head protection for drivers, via his "helmet pod" carried within the three-point cage area, to increase head protection rather than the foam plumbing insulation and leather snap-on covers the rules required. He was also one of the first to use hand/arm restraints, after breaking his arm in a crash.

Tragically, drag racing lost one hell of an innovative, creative mind there on the guardrails at Pomona in '71.

Most blame Pete's ground-effects system for his fatal crash. To refute that, I've seen Jere Alhadeff's photo shot milliseconds before Pete crashed.

Pete has the butterfly wheel turned hard-left, the drag links are bowed from his steering effort and the front tires are coming off the rims, again from the steering effort. He put his all into keeping that hot rod off the guardrails, to no avail. This tells my uneducated, non-engineer's mind that something else had gone bad-wrong... like perhaps the rear end components were galling and power-steering the car hard-right.

Too bad we'll never know the real answer to what caused this tragedy. The only one who could have explained it will be gone 30 years this Pomona Winternationals.

Jim Hill

Pete Robinson's first "Tinker Toy" was full of innovation. It was a Woody Gilmore car (Race Car Engineering) that replaced Pete's earlier Dragmaster "Dart" style chassis, which replaced Pete's original Dragmaster car in which he won the 1961 NHRA Nationals. If my memory is correct (?), this was the car on which Pete was forced, by tech officials, to install a drag chute because it obviously was capable of exceeding the NHRA imposed "150 mph mark" that separated cars from either requiring or not requiring a chute. Pete felt that a race car, even a dragster, ought to be able to stop reasonably with braking, and didn't consider a chute as a means of "saving" an out-of-control run. He was by nature a cautious person who felt the right foot should be a racer's greatest safety asset. His solution to the rule was to have a mini-chute made that fit the letter if not the "spirit" of the rules. It was, by description, about as big as a large western bandana!

Pete ran an ultra-light Ford Fairlane motor. This was a stroked 289 Ford small-block (!!!) over bored and with an "arm" to bring displacement to 352 cubic inches. Always the weight-conscious one, Pete found that he could build a Ford motor and save enough weight over the small-block Chevy to give him an advantage. He paid considerable attention to grinding and relieving ANY metal he felt was unnecessary to strength, both with internal engine components as well as externals. It could accurately be said that Pete was "fanatically obsessed" about weight saving, even to the point that before a run he would remove all his clothing (he said he did wear boxer shorts 'cause they were thinner and lighter than jockeys!) and don only his rules-required fire suit!

He ran the little Ford on gas (AA/GD) and on light percentages of nitro as an AA/FD.

From the start, Pete struggled with oiling system problems with the little Ford motors. The Ford, of course, was a purely passenger car based design and was never engineered to handle the kind of power output (supercharged, on gas or nitro/alcohol) that Pete's modifications produced. The result was a serious "appetite" for main and rod bearings, this problem being severely accelerated when Pete ran on fuel. (Hardly a big surprise!)

He finally solved those problems by enlarging the entire oiling system, rerouting more oil to the mains and rods, and building his own large-volume, high-pressure oil pump.

Ironically, when Pete went to the new SOHC 427 Ford "Cammer" he ran into more oil system problems, as did all the Ford Cammer racers who ran blown motors. (The injected nitro motors seemed to survive with only moderate maintenance) This caused considerable grief (Kalitta destroyed "truck loads" of SOHC 427's in the early days of running the Fords!), and Pete spent a considerable amount of time "bottom-end diving" to replace mains and rods that were "one-pass wonders."

The final cure for all those woes was the adaptation of the basic oiling system developed (also by much blood, sweat and burned bearings!) by Chrysler for the then-new 426 "Late Model" hemi motors. Ford guys also found their parts problems eased because they went to Chrysler style/size bearings and the Chrysler oiling systems.

Pete felt that the OHC design was better suited to nitro racing than the Chrysler hemi design, and he stuck with it even after Ford drastically reduced/eliminated funding for racing. (The shift was to reducing emissions, ala the infamous "Muskie Bill," and improving safety, followed shortly by the first "Gas Crisis" of 1973-74 that produced the equally infamous Ford Pinto) Of course, Pete's stubborn determination to show the rest of the drag racing world that the Cammer was a "Better Idea" (Ford's ad slogan in the '60s) for Top Fuel ended with his fatal crash at the 1971 NHRA Winternationals. One can only speculate as to how successful his career might have been had he survived and continued to pursue his innovative dreams.

Jim Hill

Created 2/1/19

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|